Michael Jackson was a Proud Black Man

Michael Jackson´s skin colour has changed due to an autoimmune disease Vitiligo. But he remained Black.

"I know my race. I just look in the mirror, I know I'm black!"

Michael Jackson, 2002

"People have lied on me. I'm a black American and I'm proud of it, and I'm honored of it."

Michael Jackson, 1996

"Even in personal life, he was always that uncle who taught us about black history, and preaching it. And a lot of people don´t realize that."

TJ Jackson twitter.com/always_shiplove/status/1172955251889995776?s=20

“I´m proud of my heritage. I´m proud of it. I´m proud to be black. I´m honored to be black, and I just hope one day they will be fair in portraying me the way I really, really am….just a loving, peaceful guy wanting to make wonderful, unprecedented entertainment and songs and music and film for the world. That´s all I want to do. I´m no threat. I just want to do that. That´s what I want to do. To bring joy to the world.”

Michael Jackson in a Steve Harvey radio interview in 2002

Michael Jackson always sang with a huge jumbotron pic of his young self at his concerts

“We are black, and we are the most talented people on the face of the Earth.”

Michael Jackson, as remembered by Teddy Riley

Media tryin' to tell the public that Michael Jackson did not honor his black roots? Think Again- 1993 Superbowl performance he had this banner unfurled the length of the entire football field with GoodYear Blimp overhead capturing the image.Media tryin' to tell the public that Michael Jackson did not honor his black roots? Think Again- 1993 Superbowl performance he had this banner unfurled the length of the entire football field with GoodYear Blimp overhead capturing the image.

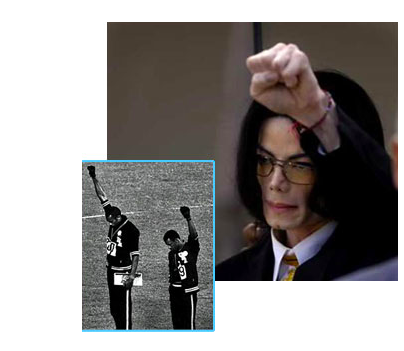

The SNCC, Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, was a civil-rights group formed to give younger blacks more of a voice in the civil rights movement. The SNCC coined the term "black power" - Michael Jackson spoke against the power that suppressed&oppressed.

“Even though he is ´different´, as the video (Remember the Time) seems to suggest, he is one with them. The implicit message to viewers is that racial identity is much more than skin pigmentation: it is about shared dances, songs, narratives, and histories.”

Joe Vogel

"Here you go: I’ve worked with Michael Jackson in his studio on and off for over 17 years – that covers most of the time that everyone seems to be fixating upon. Michael has vitiligo. I’ve seen it with my own eyes, along with the unhappiness it has caused him both privately and publicly. Many great artists are reserved off stage, but for Michael this was compounded by the media and public obsession over his appearance. He covered much of this up with make-up – and for many years hid behind a screen of uncomfortable and impractical panstick.

He’s tried to learn to be accepting that people don’t believe the transformation he’s made over the years, but all this ridiculous argument over it makes it incredibly hard for him. I see him a couple of times a year, usually just for a day or so, and even now, all the speculation and prying offends and upsets him. He is one of the most loving, kind and gentle souls I’ve ever met, and has possibly the most stoic and forgiving nature in the light of such awful injustice, slander and bigotry. He’s not without faults, and has to be one of the most exacting professionals I’ll ever have the fortune to work with. Most of the time, he ignores what people say, and in the last few years he’s gone past caring what people think. He isn’t on earth to justify how he looks – but the public seem to assume that he must account for the changes he made to his appearance, including those that he couldn’t control. I can tell you: I’ve been in a pool with him: before he had depigmentation therapy, he was blotchy all over. Now, he’s basically so white that he burns at even slight exposure to the sun. This was a choice he made: makeup or treatment, and having the money, he got the treatment. I don’t blame him – had I this condition, and the funds, I would have done it too.And let me tell you: when you get to know him, he’s a normal, easy-going (out of the studio!) guy, with a great sense of humour and is most definitely a BLACK man.

I posted here because he bet me ages ago that I couldn’t find a single site online that really addressed his skin colour in an even manner. I hope I’ve cleared up some of your questions."

Leroy

Have you noticed how Michael Jackson tried to hide his face behid his black hair at the time when his skin became significantly lighter?

Part of a conversation about love from "Glenda tapes" (1992):

MJ: But, yeah, but girl, girlfriend had my nose wide open, okay? You could drive a truck through my nose.

G: Laughs…That is the craziest expression. How did they come up with that? I am just wondering who thought of it. I don’t understand how your nose can be wide open.

MJ: I don’t know

G: But it had to come from somewhere and I just wanted to the people who made it up.

G: It’s the craziest expression I have ever heard

MJ: It’s a black thing

G: ( Laughing) Black thing? What is it with your nose? I can’t understand how your nose can be wide open?

MJ: I don’t know..(whispers – It’s just, it’s personal)

G: I mean it had to come from somewhere. Somebody had to have made it up and I was wondering what they were thinking when they made it up?

MJ: It’s a black secret.

G: Okay Laughing

Michael Jackson: A Black Man's Dream (made by @phonchrist):

Rolling Stone

In Black Or White, he bursted through flames with images of the KKK to tell the world

"I ain't scared of no sheets!"

Then Michael Jackson morphed into a BLACK PANTHER. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Panther_Party When Black or White premiered for the first time on Fox, MTV and BET, it is estimated that 500 million people watched. A staggering 1/2 BILLION people watched it.

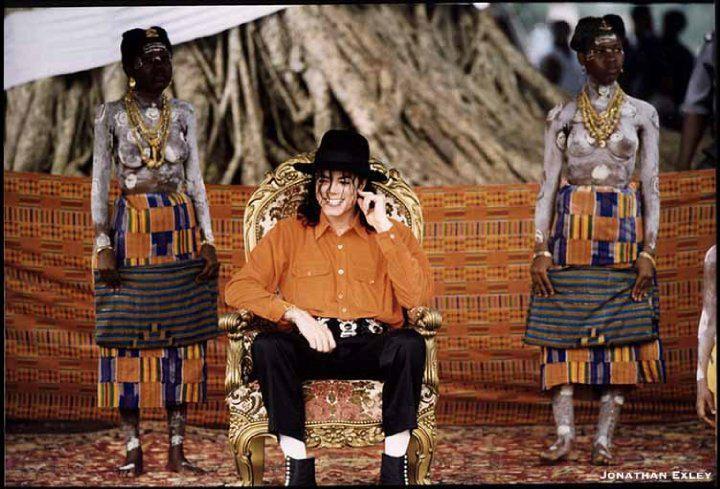

Michael´s admiration for Africa:

www.truemichaeljackson.com/more-about-michael/africa/

Michael Jackson’s hand written notes from 1987:

Michael Jackson, You Were There - Sammy Davis Jr. Tribute, 1989

Michael tried to give Little Richard his publishing rights back immediately after he bought the Beatles catalog.

twitter.com/headtoParadise_/status/786024766985662464?s=20

Paris Jackson comments:

“I want to thank Michael for opening up so many doors for African Americans, to be on daytime shows, late night shows. He allowed Kobe and I to have our jerseys in peoples homes across the world, because he was already there and he opened all those doors for us.”

Magic Johnson at MJ´s funeral

Michael Jackson´s speech in Faces,

a song Michael wanted to record for & with Nelson Madela...:

These Are The Worst Of Times And These Are The Best Of Times

Racism, Bigotry, Ethnocentricism, Prejudice, Hatred And Violence

Are Breaking The Heart Of Our Planet And Streaming Its Soul

And Yet We Are Coming Alive As Never Before

Nelson Mandela, A Black Man

A Former Symbol Of Subjugation And Slavery Guides South Africa

Democracy And Freedom Flourish As Never Before

And A New Consciousness Proclaims The Dawn Of The Age Of Enlightenment

Where Survival Of The Fittest Is Replaced By Survival Of The Wisest

Let Us Dream Of The Great And Sudden Splendent Of A New Tomorrow

Let Us Dream Of The Full Flowering Of A New Collective Consciousness

Let Us Dream Of A Tomorrow

Where We Can Hold Our Heads High

And Stretch Our Arms Toward Perfection

Let Us Dream Of A Tomorrow Where We No Longer Fragment And Fracture Our Global Village Of Narrow Domestic Walls

Where Tribalism No Longer Surfaces

Under The Routines Of Nationalism And Patriotic Fervor

And Where We Can Truly Love From The Soul

And Know Love As The Ultimate Truth At The Heart Of All Creation

Let Us Dream Of Tomorrow For Our Children Are Nurtured And Protected And Nourished

And Our Elders Revered And Honored And Venerated

Let Us Dream Of Peace And Harmony And Laughter

Let Us Dream Of Joy And Ecstasy

Let Us Dream Of Dancing The Cosmic Dance

And As We Dream

Let Us Remember

Those Who Dared To Dream The Horrors

And Sacrificed Their Yesterday

So We Can Have Our Tomorrow

Michael's speech against racism, Sharpton's National Action Network headquarters in the Harlem neighborhood of New York, July 9, 2002:

“I remember a long time ago in Indiana, [when I was] like 6 or 7 years old, and I had a dream that I wanted to be a performer, you know, an entertainer and whenever I’d be asleep at night, and my mother would wake me up and say, ‘Michael, Michael, James Brown is on TV!’ I would jump out of bed and I’d just stare at the screen and I’d do every twist, every turn, every bump, every grind. And it was Jackie Wilson; the list goes on and on you know, just phenomenal, unlimited, great talent. It’s very sad to see that these artists really are penniless because they created so much joy for the world and the system, beginning with the record companies, totally took advantage of them. And it’s not like they always say: ‘they built a big house,’ ‘they spent a lot of money,’ ‘they bought a lot of cars’–that’s stupid, it’s an excuse. That’s nothing compared to what artists make. And I just need you to know that this is very important, what we’re fighting for because I’m tired. I’m really, really tired of the manipulation. I’m tired of how the press is manipulating everything that’s been happening in this situation. They do not tell the truth, they’re liars. And they manipulate our history books. Our history books are not true, it’s a lie. The history books are lies, you need to know that. You must know that.

All the forms of popular music from jazz, to Hip Hop to Bebop to Soul, you know, to talking about the different dances from the Cake Walk to the Jitter Bug to the Charleston to Break Dancing—all these are forms of Black dancing! What’s more important than giving people a sense of escapism, and escapism meaning entertainment? What would we be like without a song? What would we be like without a dance, joy and laughter and music? These things are very important, but if we go to the bookstore down on the corner, you won’t see one Black person on the cover. You’ll see Elvis Presley. You’ll see the Rolling Stones. But where are the real pioneers who started it? Otis Blackwell was a prolific phenomenal writer. He wrote some of the greatest Elvis Presley songs ever. And this was a Black man. He died penniless and no one knows about this man, that is, they didn’t write one book about him that I know of because I’ve search all over the world. And I met his daughter today, and I was to honored. To me it was on the same level of meeting the Queen of England when I met her.

But I’m here to speak for all injustice. You gotta remember something, the minute I started breaking the all-time record in record sales—I broke Elvis’s records, I broke the Beatles’ records—the minute [they] became the all-time best selling albums in the history of the Guinness Book of World Records, overnight they called me a freak, they called me a homosexual, they called me a child molester, they said I tried to bleach my skin. They did everything to try to turn the public against me. This is all a complete conspiracy, you have to know that. I know my race. I just look in the mirror, I know I’m Black.

It’s time for a change. And let’s not leave this building and forget what has been said. Put it into your heart, put it into your conscious mind, and let’s do something about it. We have to! It’s been a long, long time coming and a change has got to come. So let’s hold our torches high and get the respect that we deserve. I love you. I love you.

Please don’t put this in your heart today and forget it tomorrow. We will have not accomplished our purpose if that happens. This has got to stop! It’s got to stop, that’s why I’m here with the best to make sure that it stops. I love you folks. And remember: we’re all brothers and sisters, no matter what color we are.”

Michael Jackson

Michael Jackson's Blackness [MJ Unmasked]

"Michael Jackson fundamentally altered the terms of the debate about African American music. He was a chocolate, cherubic-faced genius with an African American halo. He was a kid who was capable of embodying all of the high possibilities and the deep griefs that besieged the African American psyche... for America to miss that is to miss the fact that Michael Jackson argued against the very deep and profound bowels of White supremacy in the belly of American political culture... The reality is Michael Jackson's humanity is so deep, the implications and inferences of his art so monumentally and magnificently global, that nothing American television could do to besmirch his character could ever, if you will, deny the legitimate genius that he represents."

From a brilliant conversation on Tavis Smiley, with two of America's most recognized critics on Michael Jackson's cultural and social impact both globally and specificially for Black people. (30/Jun/2009)

South African iconic group Ladysmith Black Mambazo - The Moon Is Walking (End Credits) from the movie: Moonwalker by Michael Jackson:

Learn more about the group and colaboration with MJ here: www.okayplayer.com/originals/secret-history-ladysmith-black-mambazo-michael-jackson-moonwalker.html

Black King

Michael Jackson crowned as King Sani:

Black Knight

David Nordahl: This triptych was entirely Michael’s idea and it was the only painting I ever did for him with a deadline. I never asked him what the painting was for. I’m quite sure Michael was aware of the history of High Status black people. He was very proud of his heritage.

Black and White and Proud...

"Black or White" is a video that is filled with symbolic imagery that I am working on for Inner Michael, in an essay about the hidden messages in the film. The "Ghosts" film has a startling reference to the Klan with its burning torches and marching mobs. That illustrates the facts of being black in America—you were a target for violence at the hands of those who wanted you to “know your place” in the social hierarchy. As a black, you understood that you were considered a bottom-feeder. Michael Jackson’s aesthetic and work helped to change the minds and hearts of a generation, but not without conflict. He was both loved and hated; he received both affectionate accolades and death threats. And Michael absolutely understood that in order to keep his pulpit for social change, he needed to stay bold and controversial to sustain his relevance. His courage in music as a message, is unparalleled.

Until the 1960's, blacks being subjected to ridicule and stereotype was the cultural norm. The Black Panther Party was a political revolutionary movement that began in 1966 and lasted until 1975. It expanded to a social and cultural revolution with contemporary symbols like the closed fist. The “Afro” hairstyle became a symbol of the African American pride initiative begun by the Black Panthers, and punctuated by James Brown in “I’m Black and I’m Proud,” released in 1968. Michael publicly declared his allegiance to James Brown as the artist who influenced him most.

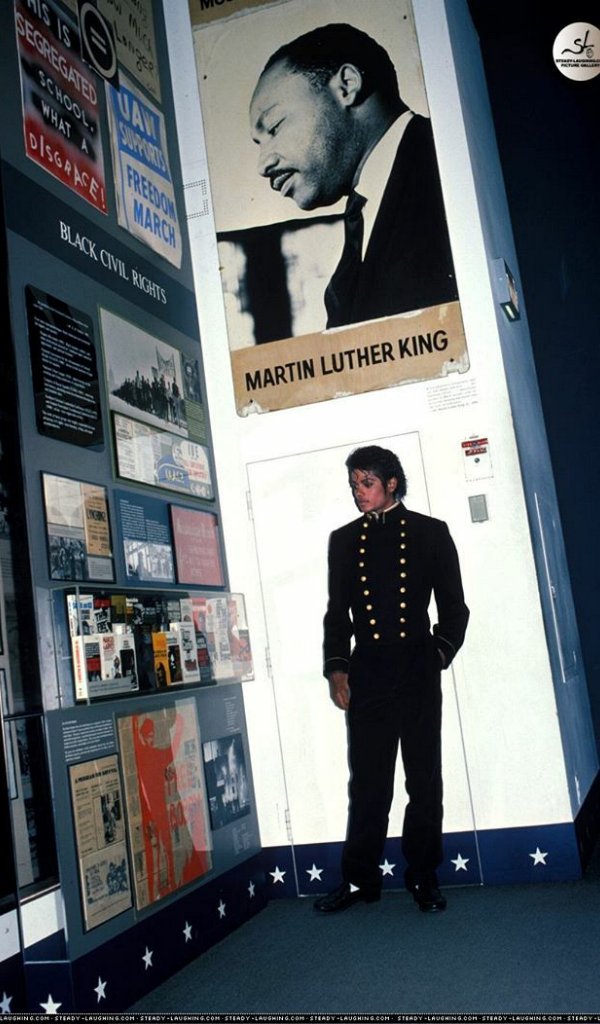

Michael truly did believe that the power to change the world lies silent and untapped within children; he grew up within the ‘kid power’ cultural message, and it explains his loyalty, affection and attention to children. He believed in youth. And it was in a unique time that Michael Jackson wove his magic into the social tapestry of his life and our history. Who Michael was, and what he contributed to civil rights in the social and cultural fabric, was relevant then and deserves to be celebrated today. While Dr. King said it in words and actions, Michael Jackson said it in music, lyrics and the images of film. Michael Jackson, like Martin Luther King before him, was a prolific and vocal freedom fighter.

By Rev. Barbara Kaufmann, December 24 – 2010

Reverend Barbara Kaufmann is an award winning writer, poet and author. She is a member of the Wisconsin Society of Sciences, Arts and Letters; Wisconsin Regional Writers; and Fellowship of Poets.

Black and White: how Dangerous kicked off Michael Jackson's race paradox

As the King of Pop’s skin got lighter his music became more politicised, and 1991’s overlooked album encapsulated this radical moment in music

However, in the early 1990s, the public were sceptical to say the least. Jackson first publicly revealed he had vitiligo in a widely watched 1993 interview with Oprah Winfrey. “This is the situation,” he explained. “I have a skin disorder that destroys the pigmentation of the skin. It is something I cannot help, OK? But when people make up stories that I don’t want to be what I am it hurts me … It’s a problem for me that I can’t control.” Jackson did acknowledge having plastic surgery but said he was “horrified” that people concluded that he didn’t want to be black. “I am a black American,” he declared. “I am proud of my race. I am proud of who I am.”

The first few minutes of the Black or White video seemed relatively benign and consistent with the utopian calls of previous songs (Can You Feel It, We Are the World, Man in the Mirror). Jackson, adorned in contrasting black-and-white apparel, travels across the globe, fluidly adapting his dance moves to whatever culture or country he finds himself in. He acts as a kind of cosmopolitan shaman, performing alongside Africans, Native Americans, Thais, Indians and Russians, attempting, it seems, to instruct the recliner-bound White American Father (played by George Wendt) about the beauties of difference and diversity. The main portion of the video culminates with the groundbreaking “morphing sequence,” in which ebullient faces of various races seamlessly blend from one to another. The message seemed to be that we are all part of the human family – distinct but connected – regardless of cosmetic variations.

The so-called “panther dance” caused an uproar; more so, ironically, than anything put out that year by Nirvana or Guns N’ Roses. Fox, the US station that originally aired the video, was bombarded with complaints. In a front page story, Entertainment Weekly described it as “Michael Jackson’s Video Nightmare”. Eventually, relenting to pressure, Fox and MTV excised the final four minutes of the video.

The Black or White short film was no anomaly in its racial messaging. The Dangerous album, from its songs to its short films, not only highlights black talent, styles and sounds, but also acts as a kind of tribute to black culture. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is the video for Remember the Time. Featuring some of the era’s most prominent black luminaries – Magic Johnson, Eddie Murphy and Iman – the video is set in ancient Egypt. In contrast to Hollywood’s stereotypical representations of African Americans as servants, Jackson presents them here as royalty.

Promised a sizable production budget, Jackson enlisted John Singleton, a young, rising black director coming off the success of Boyz N the Hood, for which he received an Oscar nomination. Jackson and Singleton’s collaboration resulted in one of the most lavish and memorable music videos of his career, highlighted by the intricate, hieroglyphic hip-hop dance sequence (choreographed by Fatima Robinson). Again, in this video, Jackson appeared whiter than ever, but the video – directed, choreographed by and featuring black talent – was a celebration of black history, art, and beauty.

The song, in fact, was produced and co-written by another young black rising star, Teddy Riley, the architect of new jack swing. Prior to Riley, Jackson had reached out to a range of other black artists and producers, including LA Reid, Babyface, Bryan Loren and LL Cool J, searching for someone with whom he could develop a new, post-Quincy Jones sound. He found what he was looking for in Riley, whose grooves contained the punch of hip-hop, the swing of jazz and the chords of the black church. Remember the Time is perhaps their best-known collaboration, with its warm organ bedrock and tight drum machine beat. It became a huge hit on black radio, and reached No 1 on Billboard’s R&B/hip-hop chart.

The first six tracks on Dangerous are Jackson-Riley collaborations. They sounded like nothing Jackson had done before, from the glass-shattering, horn-flavoured verve of Jam to the factory-forged, industrial funk of the title track. In place of Thriller’s pristine crossover R&B and Bad’s cinematic drama are a sound and message that are more raw, urgent and attuned to the streets. On She Drives Me Wild, the artist builds an entire song around street sounds: engines; horns; slamming doors and sirens. On several other songs Jackson integrated rap, one of the first pop artists – along with Prince – to do so.

Dangerous went on to become Jackson’s best-selling album after Thriller, shifting 7m copies in the US and more than 32m copies worldwide. Yet at the time, many viewed it as Jackson’s last desperate attempt to reclaim his throne. When Nirvana’s Nevermind replaced Dangerous at the top of the charts in the second week of January 1992, white rock critics gleefully declared the King of Pop’s reign over. It’s easy to see the symbolism of that moment. Yet Dangerous has aged well. Returning to it now, without the hype or biases that accompanied its release in the early 90s, one gets a clearer sense of its significance. Like Nevermind, it surveyed the cultural scene – and the internal anguish of its creator – in compelling ways. Moreover, it could be argued that Dangerous was just as significant to the transformation of black music (R&B/new jack swing) as Nevermind was to white music (alternative/grunge). The contemporary music scene is certainly far more indebted to Dangerous ( ie Finesse, the recent new jack-inflected single from Bruno Mars and Cardi B).

Only recently, however, have critics begun to reassess the significance of Dangerous. In a 2009 Guardian article, it is referred to as Jackson’s “true career high.” In her book on the album for Bloomsbury’s 33 ⅓ series, Susan Fast describes Dangerous as the artist’s “coming of age album”. The record, she writes, “offers Jackson on a threshold, finally inhabiting adulthood – isn’t this what so many said was missing? – and doing so through an immersion in black music that would only continue to deepen in his later work.”

That immersion continued as well in his visual work, which, in addition to Black or White and Remember the Time, showcased the elegant athleticism of basketball superstar Michael Jordan in the music video for Jam and the palpable sensuality of Naomi Campbell in the sepia-coloured short film for In the Closet. A few years later, he worked with Spike Lee on the most pointed racial salvo of his career, They Don’t Care About Us, which has been resurrected as an anthem for the Black Lives Matter movement. Still, critics, comedians and the public alike continued to suggest Jackson was ashamed of his race. “Only in America,” went a common joke, “can a poor black boy grow up to be a rich white woman.”

Yet Jackson demonstrated that race is about more than mere pigmentation or physical features. While his skin became whiter, his work in the 1990s was never more infused with black pride, talent, inspiration and culture.

Original source: www.theguardian.com/music/2018/mar/17/black-and-white-how-dangerous-kicked-off-michael-jacksons-race-paradox

"Am I Invisible Because You Ignore Me?"

Books about black history from Michael´s home Neverland:

Tell me what has become of my rightsAm I invisible because you ignore me?Your proclamation promised me free liberty, nowI'm tired of bein' the victim of shameThey're throwing me in a class with a bad nameI can't believe this is the land from which I cameYou know I do really hate to say itThe government don't want to seeBut if Roosevelt was livin'He wouldn't let this be, no, noAll I wanna say is thatThey don’t really care about usMichael Jackson

Man In The Mirror - Grammys 1988

"Black Man gotta make a change

The White Man gotta make a change

Red Man gotta make a change..."